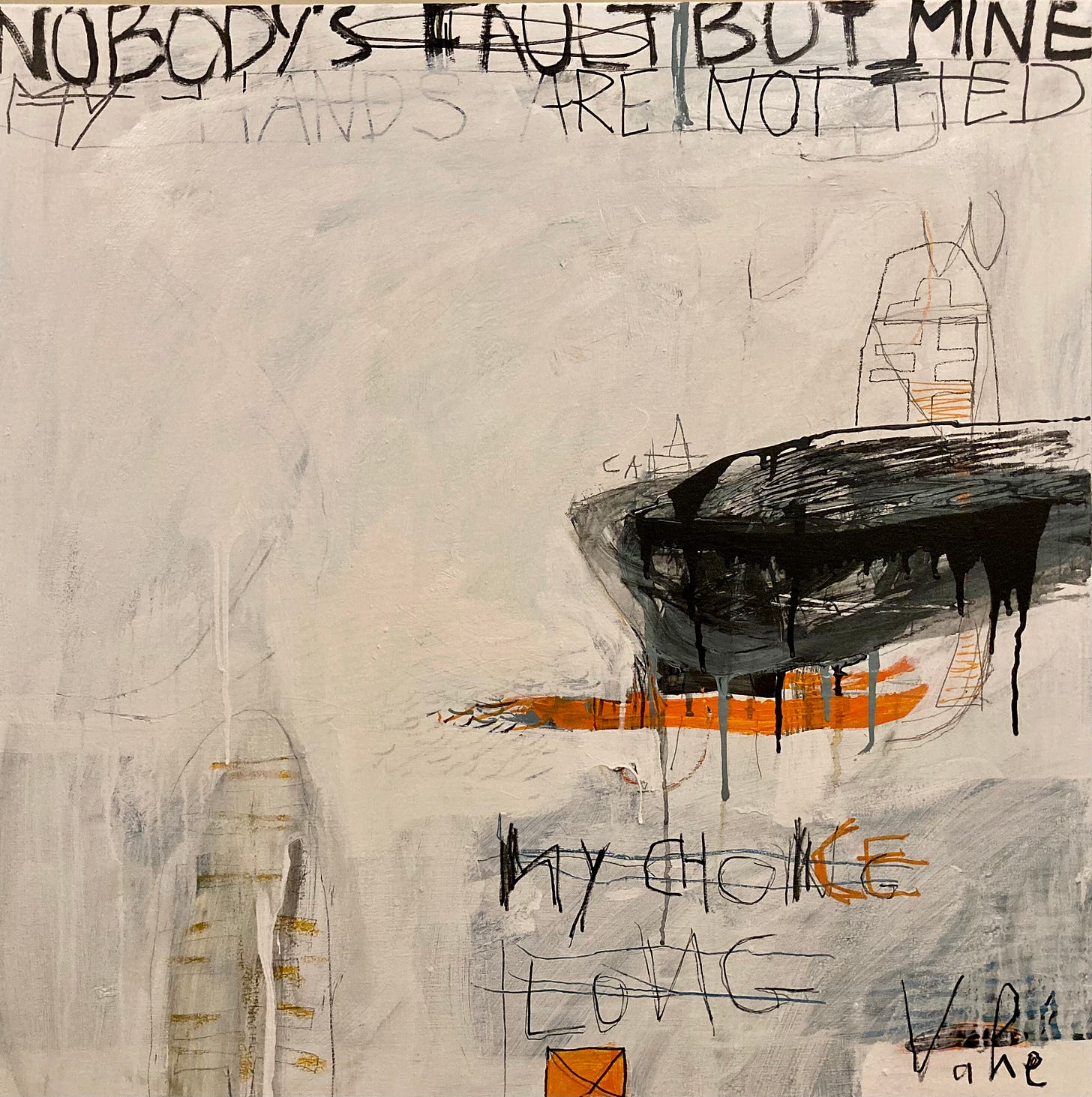

Creating Overpriced Wallpaper to Save My Soul

Art’s gasp for meaning in a world that has no need for it

If you want art to give you meaning, you’re already in the wrong place. Go water your plants, meditate with your cat, or color-coordinate your closet. Art isn’t a sermon. If you need footnotes to understand it, it’s dead on arrival. The truth is, art should hit you in the gut, make you laugh nervously, piss you off, maybe even haunt you in your sleep. If you leave a gallery yawning, then either the art failed, or you did.

Lately, I find myself asking “why?” before I do anything. I never used to have this problem. In fact, I always thought asking “why” was just procrastination in disguise, an excuse to avoid doing the very thing you’re questioning. I always believed the better question was “why not?”

I’m one of the lucky ones, my art has kept me afloat and I have a loyal following to give me the freedom to do what I love. But freedom doesn’t silence the doubt. Here I am, interrogating myself: Why should I write? Why should I perform? Why should I create anything at all? And of all the questions, the hardest one to answer is this: why should I keep painting? If I’m not communicating something through my work, then what am I doing? Am I painting in a void, mumbling incoherently to myself with colors and brushes?

After a lifetime with a brush in my hand, I’ve lost the romantic illusions about painting. The world feels more jaded than ever, and no matter how seriously I take my work, at the end of the day I worry I’m just producing commodities, overpriced wallpaper for people with money to burn.

There was a time when artists were society’s most vital communicators. Most people were illiterate; there was no radio, no television. Artists painted the revolution, the saints, the kings, the battles. When the Bolsheviks wanted to educate the masses, they turned to Socialist Realism: posters glorifying labor, steel, the proletariat. Later, even with the rise of mass media, Norman Rockwell manufactured an America where everything was pristine, jovial, and sanitized of worry.

Art carried so much weight that movements came with their own social and political convictions. Futurists, dadaists, surrealists, impressionists, expressionists…they came with manifestos. There were brutal critics who terrorized the art world, there were physical brawls between artists who came from different schools, starving for art was a badge of honor and successful artists like Dali and Chagall were branded sellouts.

Slowly but surely, progress, which is mainly defined by technology, drained the life out of art and its usefulness. The death of realism didn’t come from lazy artists, it started with the camera. Why hire an artist to capture your likeness when a camera could do it faster, cheaper, and with more accuracy? Who needed a painter to capture faces, roses, or ballerinas when a photograph could do it instantly? Who needed Delacroix, Velázquez, or Rembrandt when Kodak could immortalize Grandma in a few seconds? You didn’t need mastery, just enough shots to get one decent picture.

In this sense, the Abstract Expressionists were the last of the Mohicans. From the European pioneers - Kandinsky and Franz Marc of Der Blaue Reiter - to the New York School artists like de Kooning, Gorky, Rothko, and Pollock, they stood on the bridge between engaged art and the void.

As art grew more anemic, the ecosystem that sustained it began to erode. The role of independent critics and small galleries dissipated. The rise of mega-galleries (Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, Zwirner) and the dominance of art fairs turned collecting into investing. Publications that once set the tone ( Artforum, October, Flash Art) lost much of their bite or readership, while critics migrated to online platforms, blogs, newsletters, even Substack. The result is a chaotic scene where writing about art has devolved into a salesman’s pitch, bloated with the academic jargon of modern, postmodern, conceptual bullshit that requires interpreters to be understood, or rather, misunderstood.

Today, there are no critics as we knew it. Social media has turned anyone with an Instagram account into one. And there are no critics because there are no criteria. Anything goes, as long as you attach a half-baked story to it.

Historically, there have always been serious attempts to question the validity of art, to make art feel as urgent as life itself. But every attempt has fallen short, leaving art history stubbornly unmoved.

The most serious attempts came from the Surrealists, followed closely by the Dadaists. After World War I, Jacques Vaché, one of the movement’s enfant terribles, wrote from Zürich: “Art is nonsense.” Around the same time, the Dada poet Tristan Tzara declared: “Everything one looks at is false.” They weren’t just being nihilistic, they were announcing the slow death of engaged art itself. That’s why Vaché paraded around in a half-German, half-Allied soldier’s uniform: a walking contradiction, a living provocation, a way of saying art couldn’t sit quietly in a gallery. It had to disturb, even at the risk of ridicule, even with his own skin in the game.

In their search for profundity, artists kept trying to shock. Carolee Schneemann pulled a scroll from her vagina and read it to a stunned audience. Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped the Reichstag in Berlin like a giant Christmas present. Andres Serrano dunked a crucifix in urine (Piss Christ), igniting protests and headlines. Andy Warhol filmed a man sleeping for eight hours, eight fucking hours, and people lined up to watch. Damien Hirst floated a shark in formaldehyde. Tracey Emin displayed her unmade bed, complete with stains and cigarette butts. Chris Burden had a friend shoot him with a rifle inside a California gallery. And still, as André Breton sighed to Luis Buñuel in the late sixties: “It’s very sad, Luis, we can’t scandalize anyone anymore.”

The problem isn’t lack of effort. It’s that we, the audience, have become numb. Shock has an expiration date. Once you’ve seen it all, nothing shocks.

Does this mean any attempt to give the artist a new mission is doomed from the start? Do we have to finally admit that what we produce are commodities, pretty objects to decorate living rooms, or investment pieces for the rich and powerful to trade like stocks?

Maybe it’s too late to change the course of history. Especially now, with AI in the picture, when the line between illustration and art has become razor-sharp. The camera once captured everything you could see. AI, even in its infancy, captures everything you can imagine. Craftsmanship, skill, technique: all of it is about to be obsolete. And since painting has already lost whatever social function it once had, what’s left feels dangerously close to self-indulgence.

So why the hell do I still paint?

Because painting is sublimation. It’s cheaper than therapy, safer than murder, and the only thing I know how to do really well. Because every time I paint, I scrub a layer of anxiety, lust, anger, or love off my soul and smear it on canvas. If it makes you feel something, anything, then I’ve succeeded. And if not, screw it. At least it saved me.

So, my dear friends, if you’d like to see my work through these lenses, I invite you to join me at my gallery on Saturday, August 30, from 5 PM to 8 PM, at The Reef.

The entire building will be buzzing with exhibitions and open studios. If you believe you can be touched or moved without searching for a meaning, then you should drop in.

Address: The Reef – 1933 S Broadway, 4th Floor, Downtown Los Angeles

Maybe it’s not the art that’s dying, but our numbness that makes it harder to feel and translate.

It’s scary how numb we’ve all become. The whole world feels different, and it’s shocking that it only took less than ten years for everything to change.

Ten years ago, things felt like they had more meaning: art, music, everything. If I had read what you wrote back then, I probably would have argued with you that art never dies and that it’s everywhere. But today, I can’t. I completely agree.

Are we becoming numb? Or is everything really losing its meaning? But whatever it is, if you’re creating something and it makes you feel any kind of emotion, then as you said, you’re already succeeding.

Amazing how you have described the evolution of Art.

Possibly the shock effect through art has an expiry date similar to scrolling reels and the dopamine effect.